The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people.

This seems to occur in all societies at all scales. It is a well-studied pattern called a power law that crops up in a wide range of social phenomena. But the distribution of wealth is among the most controversial because of the issues it raises about fairness and merit. Why should so few people have so much wealth?

The conventional answer is that we live in a meritocracy in which people are rewarded for their talent, intelligence, effort, and so on. Over time, many people think, this translates into the wealth distribution that we observe, although a healthy dose of luck can play a role.

But there is a problem with this idea: while wealth distribution follows a power law, the distribution of human skills generally follows a normal distribution that is symmetric about an average value. For example, intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, follows this pattern. Average IQ is 100, but nobody has an IQ of 1,000 or 10,000.

The same is true of effort, as measured by hours worked. Some people work more hours than average and some work less, but nobody works a billion times more hours than anybody else.

And yet when it comes to the rewards for this work, some people do have billions of times more wealth than other people. What’s more, numerous studies have shown that the wealthiest people are generally not the most talented by other measures.

What factors, then, determine how individuals become wealthy? Could it be that chance plays a bigger role than anybody expected? And how can these factors, whatever they are, be exploited to make the world a better and fairer place?

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Alessandro Pluchino at the University of Catania in Italy and a couple of colleagues. These guys have created a computer model of human talent and the way people use it to exploit opportunities in life. The model allows the team to study the role of chance in this process.

The results are something of an eye-opener. Their simulations accurately reproduce the wealth distribution in the real world. But the wealthiest individuals are not the most talented (although they must have a certain level of talent). They are the luckiest. And this has significant implications for the way societies can optimize the returns they get for investments in everything from business to science.

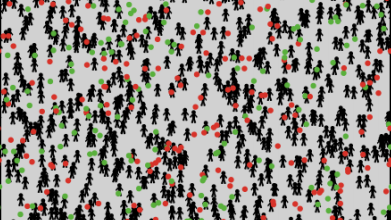

Pluchino and co’s model is straightforward. It consists of N people, each with a certain level of talent (skill, intelligence, ability, and so on). This talent is distributed normally around some average level, with some standard deviation. So some people are more talented than average and some are less so, but nobody is orders of magnitude more talented than anybody else.

This is the same kind of distribution seen for various human skills, or even characteristics like height or weight. Some people are taller or smaller than average, but nobody is the size of an ant or a skyscraper. Indeed, we are all quite similar.

The computer model charts each individual through a working life of 40 years. During this time, the individuals experience lucky events that they can exploit to increase their wealth if they are talented enough.

However, they also experience unlucky events that reduce their wealth. These events occur at random.

At the end of the 40 years, Pluchino and co rank the individuals by wealth and study the characteristics of the most successful. They also calculate the wealth distribution. They then repeat the simulation many times to check the robustness of the outcome.

When the team rank individuals by wealth, the distribution is exactly like that seen in real-world societies. “The ‘80-20’ rule is respected, since 80 percent of the population owns only 20 percent of the total capital, while the remaining 20 percent owns 80 percent of the same capital,” report Pluchino and co.

That may not be surprising or unfair if the wealthiest 20 percent turn out to be the most talented. But that isn’t what happens. The wealthiest individuals are typically not the most talented or anywhere near it. “The maximum success never coincides with the maximum talent, and vice-versa,” say the researchers.

So if not talent, what other factor causes this skewed wealth distribution? “Our simulation clearly shows that such a factor is just pure luck,” say Pluchino and co.

The team shows this by ranking individuals according to the number of lucky and unlucky events they experience throughout their 40-year careers. “It is evident that the most successful individuals are also the luckiest ones,” they say. “And the less successful individuals are also the unluckiest ones.”

That has significant implications for society. What is the most effective strategy for exploiting the role luck plays in success?

Pluchino and co study this from the point of view of science research funding, an issue clearly close to their hearts. Funding agencies the world over are interested in maximizing their return on investment in the scientific world. Indeed, the European Research Council recently invested $1.7 million in a program to study serendipity—the role of luck in scientific discovery—and how it can be exploited to improve funding outcomes.

It turns out that Pluchino and co are well set to answer this question. They use their model to explore different kinds of funding models to see which produce the best returns when luck is taken into account.

The team studied three models, in which research funding is distributed equally to all scientists; distributed randomly to a subset of scientists; or given preferentially to those who have been most successful in the past. Which of these is the best strategy?

The strategy that delivers the best returns, it turns out, is to divide the funding equally among all researchers. And the second- and third-best strategies involve distributing it at random to 10 or 20 percent of scientists.

In these cases, the researchers are best able to take advantage of the serendipitous discoveries they make from time to time. In hindsight, it is obvious that the fact a scientist has made an important chance discovery in the past does not mean he or she is more likely to make one in the future.

A similar approach could also be applied to investment in other kinds of enterprises, such as small or large businesses, tech startups, education that increases talent, or even the creation of random lucky events.

Clearly, more work is needed here. What are we waiting for?

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1802.07068 : Talent vs. Luck: The Role of Randomness in Success and Failure

TAKE UNLIMITED PAID SURVEYS

TAKE UNLIMITED PAID SURVEYS

Comments